XBEX: X-Ray Background EXplorer - Telescope Design Project

Published:

This project was a design proposal for a > 10 keV x-ray telescope. It was supposed to be a group project conducted over a single week in Tenerife, but due to the Covid pandemic the trip was cancelled and the project became an individual report.

Explanation

X-rays are photons just like visible light, but they have a shorter wavelength and are therfore much more energetic! X-ray telescopes have to be above the Earth’s atmosphere, either on a high altitude balloon, or on a satellite. This is because (luckily for us fleshy humans!) the atmosphere protects us from energetic x-rays and gamma rays, which would otherwise rip our cells apart.

Because x-rays are so energetic, it is hard to build a telescope that can focus them. Telescopes like Chandra and Nu-STAR use many concentric rings of dense mirrors, each of which gives the photons only a very small nudge. X-rays pass straight through any lens angled at more than a (small) critical angle to the direction of the incoming x-rays. The maximum angle of these lenses gets smaller and smaller as the x-ray energy increases, meaning that the telescope must be longer and longer! There are obvious size constraints when designing a satellite that has to fit into the nose of a rocket, so we can only build focusing x-ray telescopes for a certain energy range.

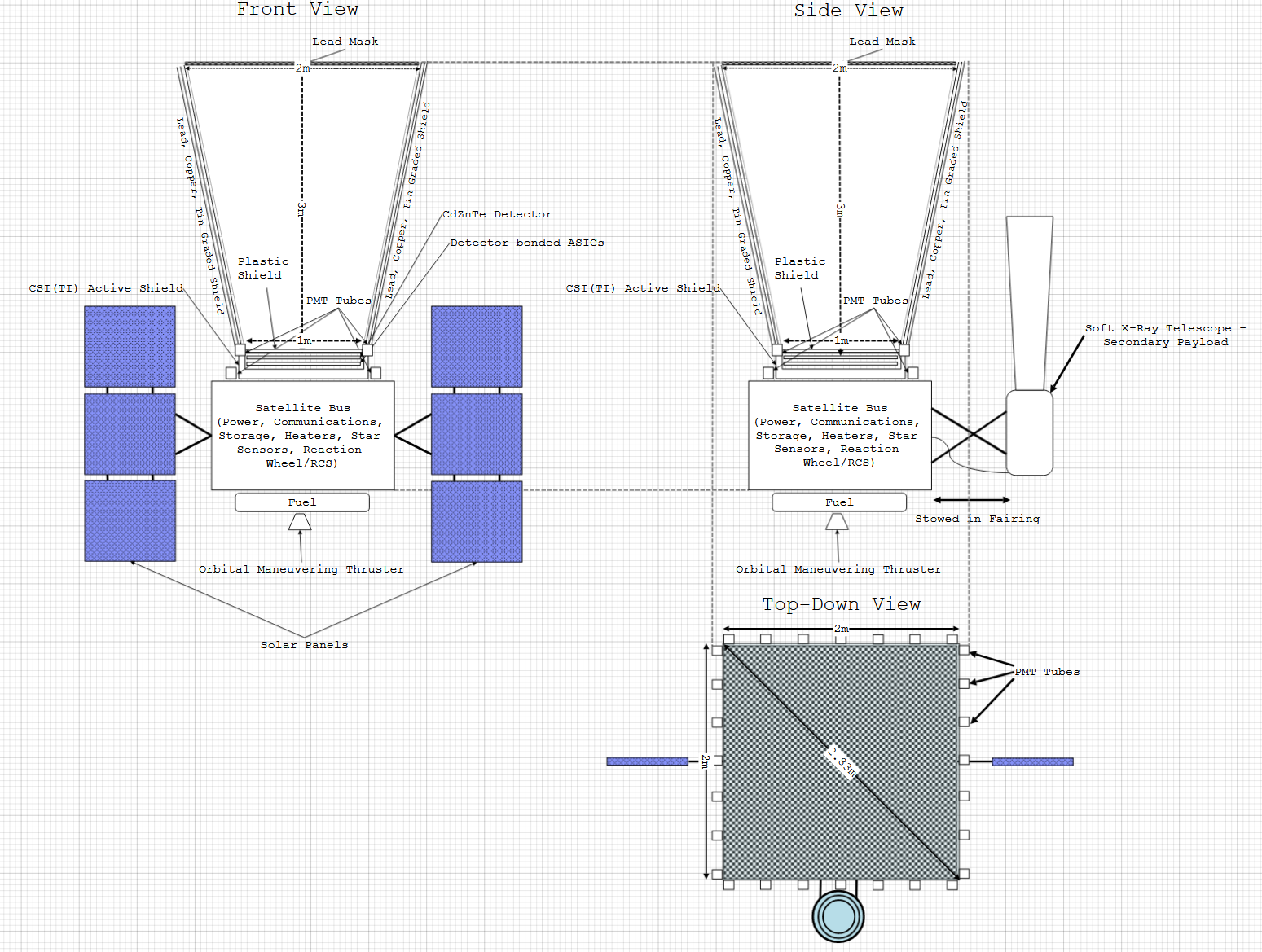

Figure showing design of XBEX satellite from 3 sides. Coded mask and detector distance and sizes are shown.

For this project I instead opted to use a design known as a coded mask. It follows a similar principle to a pinhole camera, where a small hole is punched in an otherwise opaque mask, and an image of the sky is projected on the wall behind the hole. If you replace the wall with an array of pixels, a bit like in a camera sensor but specially designed to detect x-rays instead of visible light, and you stab loads of holes into the mask randomly until half of the area of the mask is a hole (You can do a bit better than randomly, but many early x-ray telescopes used entirely random masks and worked fine). Then you can imagine you have lots of images of the sky projected onto your detector, so it would look quite messy! This is where some math comes in, but the details are not important. All you need to know is that if you know what the mask looks like you can reconstruct what the sky probably looked like by a process called convolution. This lets you take a picture of the sky, and by playing with the size of the pixels/mask holes, the distance between the mask and detector you can choose how much of the sky the telescope can “see”.

I wanted my telescope to look at lots of the sky, but also be able to tell precisely where the x-rays were coming from, which is normally a trade-off we have to make. You can’t normally have your cake and eat it! I managed to get around this somewhat by having perhaps optimistically small pixels, due to advances in manufacturing processes, which meant at least in theory my telescope can see the whole sky every 3 days, and still be able to considerably beat previous missions in source positional accuracy. X-Ray telescopes are a lot worse at this than optical telescopes, so we often can’t tell which of many nearby objects we see in a picture is actually emitting the x-rays.

XBEX is designed to resolve the x-ray background - this is x-ray light that can’t be tied to a specific galaxy or other x-ray source, and is likely emitted by a faint, distant object that we can’t see. This background is present all over the sky. The longer we look and the more sensitive the telescope the more of these x-rays we can tie to new sources, such as Active Galactic Nuclei (AGN), which lets us test theories of galaxy evolution.

An AGN a compact region at the center of a galaxy, due to a supermassive black hole millions or billions times the mass of our Sun! These AGN can emit across the whole electromagnetic spectrum, from radio waves to gamma rays, and are classified in different ways depending on how much gas in that galaxy is blocking our view of the AGN. AGN with lots of gas in the way (high column density) are called Compton-Thick AGN, because it is very unlikely any given particle of light will make it all the way through the gas without interacting with it. This makes Compton-Thick AGN harder to detect because a lot of the less energetic emission is blocked by this pesky gas, so we need to look at high energy x-rays which can make it all the way through! We’re interested in Compton-thick AGN because they are often under-represented in surveys, and it would be useful to know if as we look further away (further back in time!) whether we see more or less of them compared to “normal” (Compton-thin) AGN. This could tell us whether our current ideas about how galaxies evolve and how the AGN interacts with its host galaxy are correct.

If you’d like to learn more, the Executive Summary (like an abstract) is below, and there is also a link to download the full paper.

Executive Summary

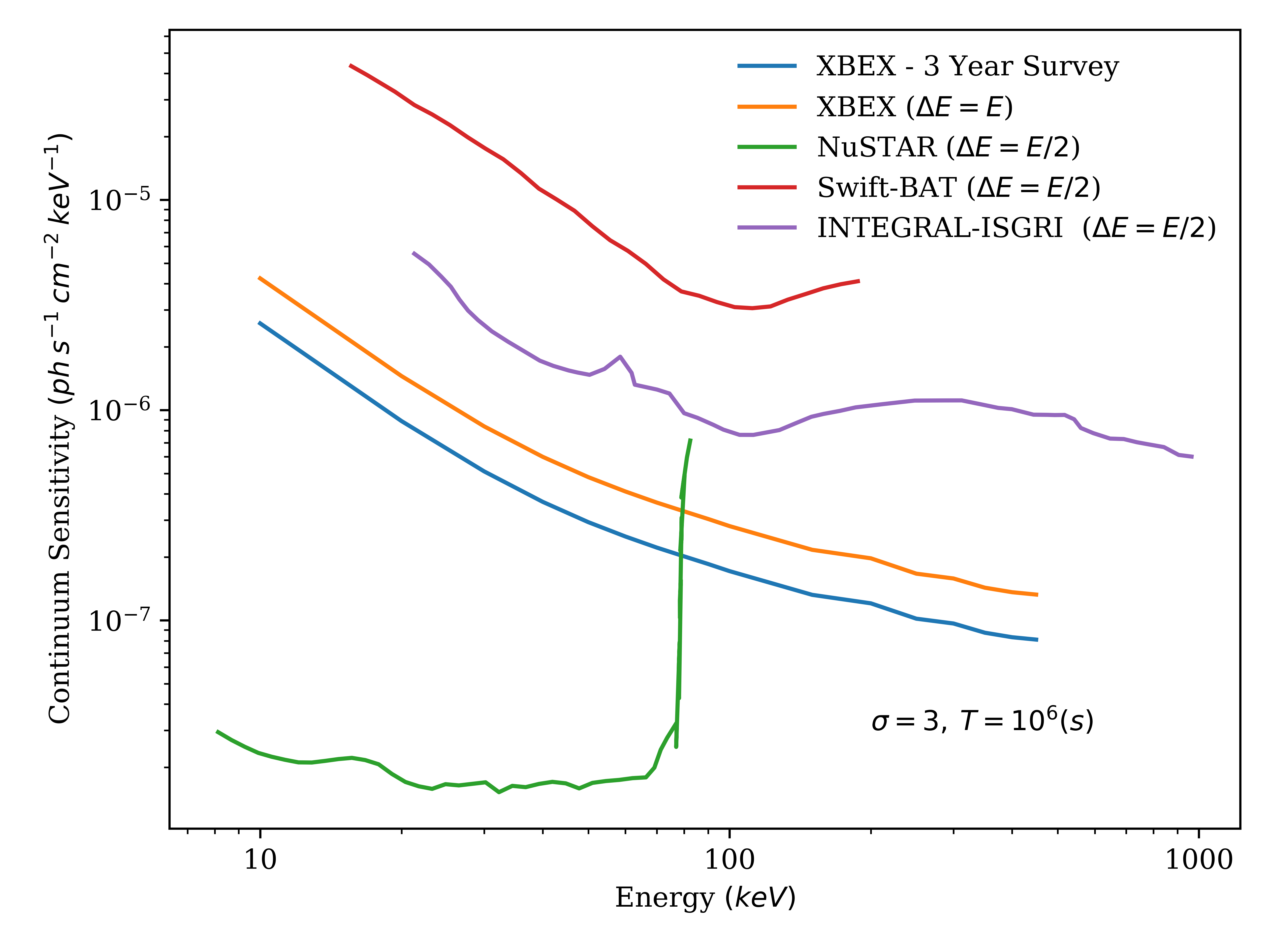

XBEX is a hard x-ray all-sky survey mission that will be sensitive across the 10-300keV range for imaging and spectroscopy. It will primarily investigate the x-ray background, with the mission of resolving many more of the individual sources that contribute to its non-stellar continuum. XBEX will catalogue an order of magnitude more AGN, including Compton-thick AGN, than it’s predecessors, including the Swift and IN- TEGRAL telescopes. In their all-sky surveys, Swift has observed around 1600 hard x-ray sources (Oh et al., 2018) and INTEGRAL has discovered around ∼1000 emitting objects (Bird et al., 2016), whereas XBEX is expected to catalogue over 10,000 extragalactic sources during its 3 year survey, including between 700 and 2000 new Compton-thick AGN. XBEX has 4x times better continuum sensitivity than INTEGRAL or Swift across its energy range.

XBEX will conduct the most unbiased survey of the deep extragalactic sky, and will identify many more Compton-thick AGN at intermediate redshift, allowing investigation of the true proportion of AGN that are Compton-thick, and whether this proportion changes with redshift, which would have a large impact on theories of AGN evolution and the link between AGN and their galaxies. XBEX will also watch for new transient sources, and allow us to more accurately study new classes of object, such as x-ray bright optically normal galaxies (XBONGS). The science payload consists of a coded mask telescope, using a square twin-prime uniformly redundant array (URA), which has the benefit of having a delta-function for its point spread function, rather than the noisy sidelobes associated with a random mask. The detector is comprised of 4445 1.5 x 1.5 x 1cm CZT crystals, each of which is subdivided into 225 “virtual” 0.1 x 0.1 cm pixels, which will make XBEX the first megapixel hard x-ray telescope with a total detector area of 10, 000cm 2 . This massive step up in the number of detector crystals is due to recent advances in the growth of CZT crystals, and the development of very power-efficient readout electronics. The use of a large number of small pixels makes it possible to have a large detector area, which allows for good sensitivity, while the small pixel size means the detector has high spatial resolution, which means this telescope has a much better angular resolution and point source location accuracy than its predecessors. XBEX will have an angular resolution of 3.4’, and a PSLA of 14”. The half coded field of view of the telescope will be ∼36 ◦ by ∼36 ◦ , and the telescope will observe the whole sky every ∼48 hours.

The mission will also have a secondary payload of a soft x-ray telescope, which will perform compli- mentary observations in the 0.5 - 10 keV energy band, including characterising the the column density of the AGN observed in the hard x-ray band, and observing the 6.4keV fluorescent iron line, which is another indicator of obscured AGN.

XBEX will launch in late 2027 on an Ariane 6.2 mission from Kourou, French Guiana, as part of a ridesharing mission, and will go into an low equatorial (i= 0 ◦ ) orbit at around 600km. This orbit will afford the spacecraft protection from some cosmic rays by being inside the Earth’s magnetic field, while also being high enough to remain in orbit for its nominal 5 year mission without excessive orbital decay and mostly avoid the South Atlantic Anomaly (SAA). The science payload has a mass of ∼3560kg. The 5 year mission will consist of a 3 year all-sky survey, and 2 years of specific pointings and time for guest observers.

<h5This plot shows the relative sensitivities of XBEX and other actual missions at different energies. You can see it isn’t as sensitive as NuSTAR, but it does extend to much higher energies which currently isn’t posible with grazing-incidence telescopes like Nu-STAR. </h5>

<h5This plot shows the relative sensitivities of XBEX and other actual missions at different energies. You can see it isn’t as sensitive as NuSTAR, but it does extend to much higher energies which currently isn’t posible with grazing-incidence telescopes like Nu-STAR. </h5>